A picture paints a thousand words, but what about an insurance policy? Milliman’s Michael Meehan takes a look

When it comes to the language in insurance policies, it can pay to be fluent. Fluency in this case means not only understanding the language contained in a policy, but also recognising when key details may be missing. If an insured entity just ‘gets by’ in the arcane language of the insurance policy, or only understands ‘broken insurance’, the unexpected (and unfortunate) may happen.

The general premise of any insurance policy is, ‘in the event of X, we will pay up to Y’, but insureds can find themselves responsible for losses they originally thought were covered under the terms of the policy. This often occurs when the insured simply assumed it was covered and didn’t take the time to read the policy, or misinterpreted the policy language, perhaps because something was not clearly spelled out.

Examples of this have been prevalent in personal lines since insurance was first conceived. Insureds might incur losses to personal property such as their homes, and then learn their claims were denied because of an exclusion indicating the cause of loss was not actually a covered peril. In these cases it is often not the language in the policy that is the problem, but rather, the insured either wasn’t aware of the exclusion, or didn’t understand it because it lacked clarity or details to explain what was actually intended by the insurer.

The same sorts of situations can be found in commercial policies, too. Today, insurers as well as insureds are getting more and more creative and sophisticated about how they craft policy language. The result is that it can sometimes be difficult to determine responsibility for who pays, when they pay, and how much they pay. In fact, there are situations where the order in which claims are paid can have a direct impact.

For instance, let’s assume that the company ABC is the parent company of a wholly owned captive insurance company. The captive insures the excess professional liability exposures of ABC on a claims-made basis. Under the terms of the policies, ABC has a per occurrence and an aggregate deductible of $1 million.

The captive provides coverage of up to $3 million per claim, attaching at $1 million per occurrence, with an aggregate limit of $3 million. So, for example, if there was a $5 million claim, ABC would pay the first $1 million, and the captive would pay the next $3 million—its aggregate limit above the $1 million attachment point. Think of the attachment point as a deductible, so unless a claim exceeds that amount, the captive is not exposed.

This is a fairly common situation in today’s world. However, the increasing creativity of the language detailing the terms of policies is presenting insureds with new complexities. Some policies are now endorsed to include a maintenance self-insured deductible (MSID). An MSID essentially acts as a modified self-insured layer once an aggregate limit has been reached. The result is that the attachment point of the insurer(s) is modified as well.

Let’s assume that ABC has an MSID of $250,000, would retain the first $250,000 for each claim, once its $1 million aggregate deductible is exhausted. Under the terms of the insurance agreement with the captive, the captive would now attach at $250,000 for each claim and provide coverage up to its per occurrence and aggregate limits. In arrangements such as these, the order in which claims are paid can affect which entity is responsible for payment of a claim and how much it is responsible for.

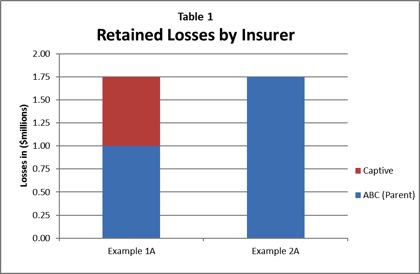

For instance, if there were three claims, each with a value of $250,000, ABC would pay each claim, thus exhausting $750,000 of its $1 million aggregate deductible. If there were then a fourth claim with an incurred value of $1 million, ABC would pay the first $250,000 (thus exhausting the $1 million aggregate deductible) and the captive would attach at $250,000 and pay the remaining $750,000. For any additional claims in the policy year, the captive would attach at ABC’s MSID of $250,000 and pay up to its aggregate limit of $3 million. In this scenario, ABC has paid a total of $1 million—its $1 million aggregate deductible, and the captive has paid $750,000. We will call this Example 1A.

Now, in Example 2A, we simply switch the order in which these claims are paid—the $1 million claim gets paid first, followed by the three $250,000 claims. In this case, ABC would pay the entire $1 million claim, exhausting the $1 million aggregate deductible, and bringing the MSID of $250,000 into play for any subsequent claims. The next three claims would also be paid by ABC as each one would fall within the $250,000 MSID. As a result, ABC would end up paying the entire $1.75 million, while the captive would pay $0.

The retained losses by entity from Examples 1A and 2A are illustrated in Table 1.

One might argue that, in these examples, the dollars are simply being shifted between two affiliates and that it has a net effect of $0 to the entities on a combined basis. If we ignore all the other impacts of dollars being paid by one entity versus the other (such as taxes, investment income, etc), that is essentially true. In this situation, the only one that may be concerned would be the captive insurance regulator.

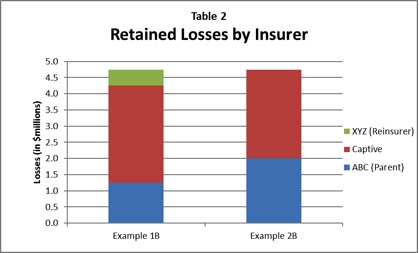

Typically these types of arrangements include a third party: a reinsurance company. Let’s look at the situation again, assuming that reinsurance company XYZ provides reinsurance coverage to the captive, which attaches once the captive’s aggregate limits of $3 million have been reached. Under the terms of the policy, XYZ’s exposure to loss could vary depending on the order in which claims are paid, and could thus affect how much it would pay for claims.

Returning to Example 1A from above, let’s consider a fifth claim with an incurred value of $3 million, which is to be paid last. Under this scenario, which we will call Example 1B, ABC would pay the first $250,000 of this new claim, the captive would then attach at $250,000 and pay the next $2.25 million, thus exhausting the entire $3 million aggregate limit.

At this point, XYZ would attach at $2.5 million on the particular claim (as opposed to the original attachment point of $4 million, assuming no other claims), and pay the remaining $500,000. As a result, ABC will have paid a total of $1.25 million, the captive their entire $3 million aggregate limit, and XYZ $500,000. Further, XYZ would now attach at $250,000 on any additional claims in this year (now a much lower attachment point than the original $4 million).

We will now introduce this same new claim to Example 2A from above, and again assume it is to be paid last. Under this scenario, which we will call Example 2B, ABC would pay the first $250,000 (the MSID), and the captive would attach at $250,000 and pay the next $2.75 million. As a result, ABC will have paid a total of $2 million, the captive $2.75 million, and XYZ $0. Further, XYZ would now attach at $500,000 on the next claim (after the $250,000 MSID of ABC and the remaining $250,000 of the captive’s aggregate) and at $250,000 on any additional claims.

The retained losses by entity from Examples 1B and 2B are illustrated in Table 2.

Using the same block of claims, the result is that the amount paid by each entity varies based solely on the order in which the claims are paid. In the examples with the XYZ reinsurance company, this becomes particularly important as it is no longer limited to the shifting of dollars between two affiliated companies. Rather, the interests of multiple entities that have no affiliation beyond the captive insurer/insured relationship are affected.

The policy language in these situations is often unclear, introducing the sort of uncertainty that could ultimately lead to manipulation, where the interests of one party are favoured over those of another. For example, if the policy doesn’t specify how claims should be ordered, such as report date, accident date, date of first payment, or settlement date, this may lead to disputes between the reinsurer and the insurer.

Using the settlement date as the method for ordering the claims as an example, who handles claims becomes a significant issue, particularly if they are handled by one of the entities that would be affected by the order in which they are paid. When even one party involved disagrees on the interpretation of its responsibilities, the whole thing can wind up in court. Interpretation of the applicable language in policies should be what dictates any decision.

When there is no clear language or guidance on how a particular feature of the policy is to be interpreted, it would likely fall on the courts to make reasonable determinations. Perhaps report date, accident date, date of first payment, or settlement date are to be used. Regardless, it’s better for all parties that participate in the kinds of insurance and reinsurance agreements described here to make sure that who pays what, and when, is spelled out clearly up front.